- FootBiz

- Posts

- FootBiz newsletter #125: The alarm bells are ringing for domestic league broadcast rights in Europe

FootBiz newsletter #125: The alarm bells are ringing for domestic league broadcast rights in Europe

But they'll never be heard by those with their fingers in their ears

We’re going deep on the football and media nexus today, where there are a few different threads from different stories sort of wrapping together.

And it kind of all sprouted from a simple thought exercise: What do the big new Champions League deals mean for football?

Obviously the world has known for years now that traditional cable and satellite TV providers were on the way down 📉 and the long-promised arrival of the saviours streamers 📈 with their deep pockets and huge audiences was the future everyone was essentially praying for.

In the last week this has at least shown some signs of becoming a prophesy fulfilled, as it emerged Netflix were a big bidder for the Champions League rights that were actually won by Paramount+, a streamer that had only previously been particularly active in North America, Brazil and Australia, but which now becomes a significant rightsholder across Europe’s five biggest territories as it eyes global growth via football.

Having the world’s biggest streamers competing as serious bidders for the first time is significant. There’s no doubt about that. The question increasingly is whether they will still be here bidding up rights for anything that isn’t the most valuable club competition on Earth.

There are mixed opinions in the marketplace over the Paramount/UC3/Relevent process more broadly. Many believe that UC3 got a better price than expected for the Champions League packages, and thus did their job, though the original aim of finding a monster global deal obviously did not come to fruition.

Paramount has recently become a major player in global football broadcasting

Given the overall flattening (or decline) we are seeing in many broadcast rights deals in European football, getting a bump isn’t insignificant.

More broadly, though, selling the Champions League rights were unlikely to ever be a massive challenge. The elite sporting products are selling well and booming, in line with the wider trend of the richest getting richer. To find where the real stress is in the football-media ecosystem you need to look just a little further down.

At the Union of European Clubs’ forum last week, president Alex Muzio made an interesting point which wasn’t really a football point at all, it was a media one.

The reality is, of course, that football and media are forever intertwined. The business model of football — as it currently exists, anyway — needs media.

One of the most influential tech blogs, Stratechery, published the definitive piece on the great unbundling nearly a decade ago, explaining and predicting the aforementioned decline of cable/satellite and rise of streamers.

With the technology that facilitated the rise of those streamers has come much more accurate audience data, and an ability to better calculate key subscription metrics such as the cost to acquire each customer (CPA), the average revenue each user brings (ARPU) and their lifetime value (LTV).

Paramount has already driven a lot of subscriptions Stateside through UEFA rights

Those metrics showed that the relationship between cost of rights acquisition and viewership did not have a linear correlation. That is to say, they are better off chasing ‘big ticket’ sporting events because they disproportionately outperform the second-tier and mid-tier events.

The knock-on effect? The Champions League, the Premier League, La Liga… these leagues will always be fine as people will sign up just to watch that.

As FootBiz understands, per a source, the Premier League has been responsible for driving more subscriptions to Peacock, the NBC streaming service, than any other content (Yellowstone is second). The Champions League has been such a success for Paramount+ that they’ve just sunk over a billion dollars into expanding that offering to five new territories.

But what does that mean for leagues outside the elite?

Or, as Muzio put it at the UEC forum:

“Bundlers need to have something in their package that people ‘must have’. That is how their business model works.

“For [National Associations] from 5 to 20 since the advent of the internet that was the domestic league. They were the needed item and [TV rights] became a stable part of the clubs budgets.

“I fear that we are all beginning to see that this is starting to no longer be the case… and it is the big four leagues or the Champions League in more and more countries.”

Pictured: National Associations 5-20

The UEC are sounding the alarm on what really is a media issue, but which could have a big knock-on effect on football.

Why would a streamer, almost certainly based in the United States, bother to bid on — for example — the rights to broadcast the Swiss league in Switzerland (which has no value to any other part of their business) when they could bid to show the Champions League or Premier League in Switzerland? The logical conclusion is a bifurcation in who bids for those elite rights (huge global streamers) and who bids for domestic broadcasting contracts (nationally focused telecoms companies) but that doesn’t really solve the issue of the bids themselves. While one group of rights goes up in value, the other goes down. While one group of companies continue to scale and grow, the others scratch around to survive.

As a solution, the UEC proposes something akin to a luxury tax to protect the majority of teams who aren’t playing continental football, but only in countries where broadcasters are unloading more on external competitions than their own.

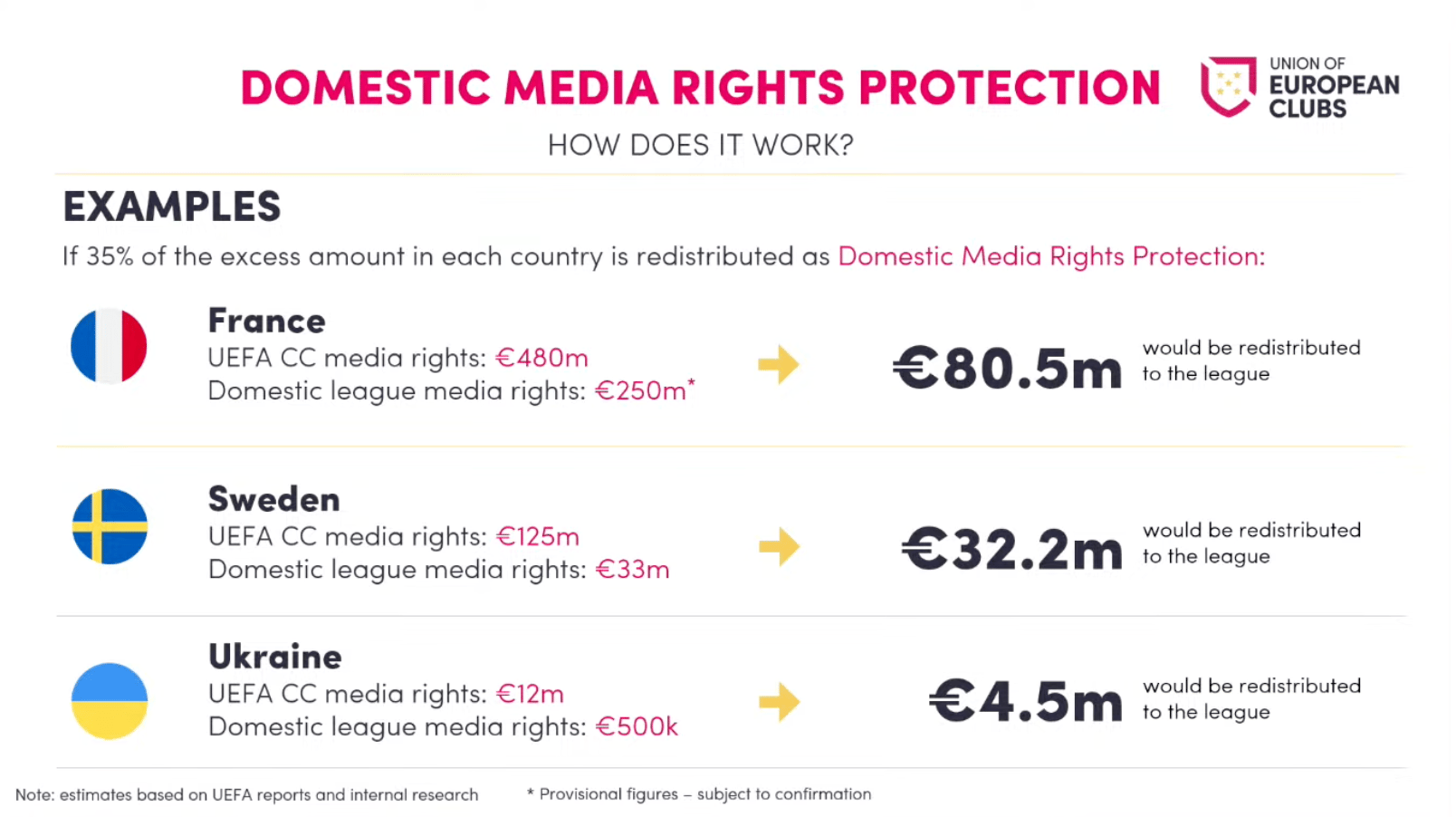

"If a country spends more money on UEFA club competition [broadcast] rights than its own domestic league then a percentage — 35% is what we've calculated — of that surplus would be set aside as media rights protection,” said Muzio.

“Those funds would be redistributed to the relevant national association to help preserve competitive balance.

“So instead of again the top teams in the leagues moving further away [from domestic rivals] because of their UEFA money, it would be more evenly distributed.”

France, Sweden and Ukraine were used as examples but (according to UEC numbers) this would help 30 European leagues by redistributing more than €200m.

Without significant action, whether it’s the policy outlined by the UEC or not, it is easy to see how the direction of travel could be very damaging for domestic football in UEFA nations.

“This is a big problem for European football,” added Muzio.

“It will be compounded by the greed of the biggest clubs in the smallest leagues.

“Obviously they’ll only fight for more cash in their own backyard as they’re the big boys; but they won’t fight for less in [continental] competitions where they aren’t the big boys.”

Celtic, Club Brugge, Sparta Prague, Rosenborg… I think he’s talking to you.

Beyond the prayed-for arrival of the streamers to save everyone’s revenues, the direct-to-consumer (DTC) model has long been touted as another path for football’s future.

And we have the first indication of how Ligue 1 has done since going it alone and launching their own service.

As covered ad nauseum on these pages, the French league’s deal with DAZN last season meant clubs would share $575m between them (not bad, but still way below the €1bn originally promised by president Vincent Labrune) in the first year.

After the collapse of the DAZN deal, and Ligue 1’s full-steam commitment to running its own DTC operation, those same clubs will instead split… $166m this year.

How French clubs are expected to suddenly make up a shortfall of ~€20m per club is a mystery.

DAZN exited their Ligue 1 deal after just one season

You can see how the future could, in a vacuum, be better in a DTC environment but the reality right now is that these clubs are hurting because of poor governance at league level and a macro media rights environment that is anything but healthy.

What’s more, DAZN are now trying to get out of another key European domestic deal that they signed in Belgium, where the runout is less clear. They signed up on the understanding that a the league format would be changing, and were warned that getting rid of the championship playoffs would result in fewer games between the big clubs (which is ultimately what DAZN were paying for) but went along with the plan because it was being pushed by the league’s bigger clubs and they assumed their interests would be aligned. They ignored the warnings and are now trying to bail on yet another agreement, the sort of behaviour that would give any future partner significant pause when considering a bid for DAZN.

You can safely assume the viewership metrics they monitor are probably not good, but if they successfully bail on Belgium and the Pro League has to go the same route as Ligue 1 then a similar dip in revenue (72% in France) would almost certainly send a number of clubs bankrupt.

It’s just a reminder that while the headlines may focus on big numbers and paint a picture of health, the reality across the continent seems to be a lot more fragile. The future is still uncertain.

Or as a cynical look:

In a week of good news for the finances of football clubs, the streamers are here and they’re bidding billions.

In a week of bad news for the finances of football clubs, all that money is going to go to the richest teams, who are becoming increasingly reluctant to share it.

Much to ponder. Much to fix. All delicately interlinked.

Table of Contents

Sorry, long old intro today but there’s still plenty below the line for subscribers.